“Education is the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel.”

Socrates

Schools will never be the same after COVID-19.

For the first time, many educational institutions have to radically rethink the process of learning from the ground up. As we struggle with possibly extended periods of physical distancing and the inequalities in access to digital learning, schools will have to contend with the “new normal” in ways that will reshape classes, lectures, assignments, and grading for future generations.

With so much uncertainty around learning these days, I wanted to revisit the core objectives of education. After graduating from university in 2016, I’ve had a few years to assess what should have been really important to me as a student back then. And from those years in formal education and from these tumultuous years in the “real world”, I’ve distilled six make-or-break questions that I should have kept asking myself as a student.

My hope is that students – and those who support them – can use these questions to help them take control over their own education, formal or not. As schools gradually transform, students will also have to, and in this “new normal”, the education we need must be adaptable, practical, growth-oriented, and driven by values.

An important caveat: Students and young people today are in the middle of an unprecedented crisis which poses tremendous burdens on their physical, mental, and emotional health. At the same time, millions of students from countries like the Philippines struggle to learn with no access to the internet, phones, and even books. We cannot expect students to thrive when they can barely survive. But in building the new norms in education, we – students, teachers, parents, relatives, friends, volunteers, policy-makers – can re-evaluate what the education system should aim for so that (1) on an individual level, students themselves may create learning systems and seek alternatives (if they can) and so that (2) on a wider scope, we can all work together to create better learning policies and environments for students, especially for those who have less of the resources.

The Six Questions

“The illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn.”

Alvin Toffler

As an overview, here are the six questions:

- Am I too fixated on my grades that I am losing track of other learning opportunities?

- Am I making enough mistakes and taking enough risks?

- Am I learning to learn?

- Am I investing enough in my communication and personal finance skills?

- Am I taking in different viewpoints, or am I embedded in communities that just echo what I know and believe?

- Am I learning and practicing good values?

In expounding on the questions below, I include insights from experts and authorities and anecdotes from my own life that shed light on why each question is important.

1. Am I too fixated on my grades that I am losing track of other learning opportunities?

Looking back, the best thing I did for myself back in university was not to slavishly devote myself to having the best grades but – surprisingly – to work in a non-profit organization. I still wanted to get good grades, but the rest of the time was carved out for meeting people, asking help from other NGO’s and businesses, working with volunteers, raising funds, and creating marketing campaigns.

My classes helped me build knowledge by learning, but my time working helped me build wisdom by experience. The latter admittedly provided me with a better grip of different skills – managing a team, communicating effectively, budgeting my time wisely – which I needed post-graduation.

In a system that still uses grades as a primary tool for evaluation, it’s hard to advice students to completely ignore them (for now). However, students should be reminded that grades are not everything and should not be the most important outcome of their education. Studies have shown that fixating on grades can lower confidence in students, prevent them from taking on more challenging tasks, and put off creative approaches.

Some countries known for their grade-obsessed cultures have even taken notice. Singapore, for instance, is now advocating for a learning model with ‘less emphasis on grades’. I had the privilege of hearing first hand from Singapore Minister of Education Ong Ye Kung during the 2018 Singapore Summit. In his speech then, he said:

“As knowledge becomes more accessible and learning is lifelong, there is less need to frontload knowledge transmission during the formative education years. Increasingly, it is human skills, including essential soft skills, that carry a premium. You can Google knowledge, but it is hard to Google skills, experience and knowledge. Finally, because a lifelong pursuit of learning and knowledge is not easy, we must cultivate curiosity and passion in our students, to drive their desire to learn for life.

“We probably have to move even further away from extensively rigorous academic teaching and assessments, towards applied learning, cultivating creativity and critical thinking. We need to emphasize less on examination scores. We need to deliver differentiated teaching, while ensuring all students have a mindset of growth and achieving excellence.

“We are entering a new era in education, reinventing the way we prepare our young for adulthood and beyond, and this is a long-term endeavor.”

With enough commitment and focus, there are a multitude of opportunities to learn and practice skills both inside and outside the confines of school, whether it’s joining a club, volunteering for a non-profit organization (like I did), taking an internship, starting a business, or even working for one’s parents or family.

2. Am I making enough mistakes and taking enough risks?

To become better at something, one must initially suck at something. To win a few times, one may fail several times too. And that’s where a healthy appetite for risk comes in.

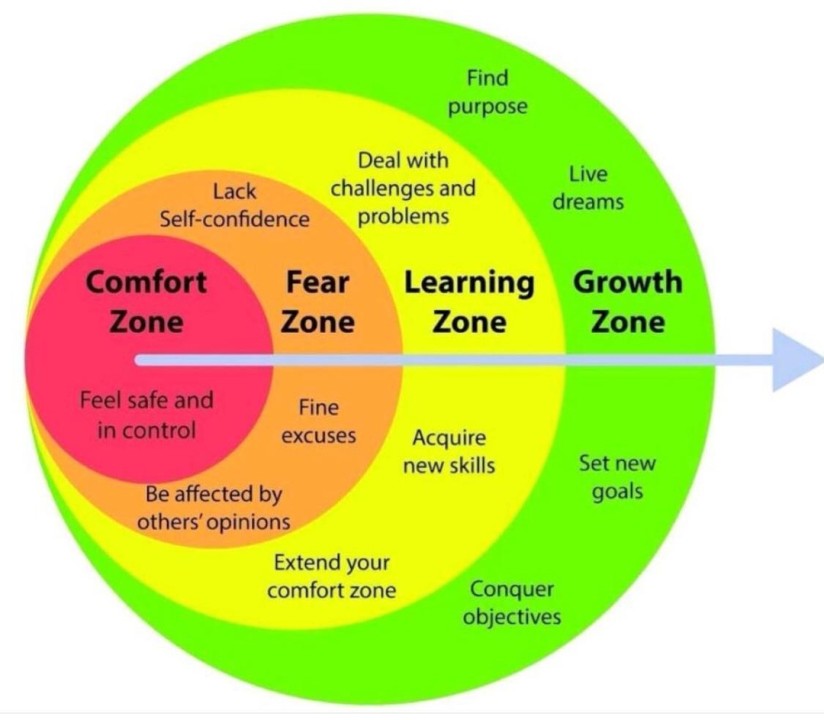

Unfortunately, our traditional education system doesn’t typically teach us how to manage risk; it rewards drawing between the lines, following the rules, and conforming to certain standards. There are few opportunities to try something new, make mistakes, and venture out of the school’s comfort zone. If we zoom out, it’s not just schools – but also certain parenting styles (see: “helicopter parenting“) – that excessively restrict young people’s appetite for risk.

Ronald Beghetto, an expert on creativity in education, encourages what he calls “beautiful risks”. Seen from the perspective of an educator, a beautiful risk, he shares, consists of “taking actions that have the potential to make a positive and lasting contribution to the learning and lives of others”. In schools, these risks involve creating more opportunities for creative expression, establishing a culture in which students are not afraid to fail, and constantly encouraging students to explore new ideas.

For students, learning to manage risks can come in different ways. In my experience, my first conscious step out of my comfort zone happened when, after reading the biographies of many leaders and figures I admired, I learned that success can only come if you take risks. And sometimes, the bigger the risk, the bigger the success. The second step was to actually take those risks and painfully learn to manage fear, self-doubt, failures, and victories along the way.

As master risk-taker Richard Branson – a guy who built a billion-dollar conglomerate from scratch, attempted several world records in boats and hot air balloons, and has as many massive failures as he has successes – says, “Those who achieve great things are the ones willing to be scared but not scared off. If you dream big and take risks, impossible becomes just a word.”

3. Am I learning to learn?

We spend at least a decade and a half learning in school, and yet we’re not really taught how to learn.

Midway through university, pressured with numerous academic and non-academic responsibilities, I decided that I had to learn and study more efficiently in school. I needed to use less time and put less effort but somehow come up with the same or better results. I struggled with this for a while until I learned about people like Cal Newport.

Cal Newport is an icon in efficient studying and learning. While reflecting on his academic journey as an undergraduate until completing his PhD in computer science from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), he wrote several books to help students maximize their time in school. What helped me the most from his books and blogs were his study hacks: insightful pieces of advice on how to retain more information from classes without spending excessive amounts of time studying.

In his own words, “Studying is a skill. If you get good at this skill, you can earn much better grades while spending much less time studying than your peers. The fact that more students don’t take this reality seriously still baffles me — they’re literally wasting dozens of hours a week on unnecessarily inefficient work.”

From his study hacks, I’ve learned how to avoid procrastination, take notes effectively, manage my time and more. Had I learned that these ideas existed, I would have saved way more time and effort throughout years of schooling. Since each person has his or her own learning style, I advice you to explore his blog archives and see which tips may work for you.

Other thinkers who’ve greatly helped in how I manage productivity are Scott H. Young (who has another terrific blog about learning) and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (who wrote the pioneering book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience).

Identifying efficient ways to learn has not just helped me in school. This has also helped me enjoy the learning process more and find exciting ways to learn even as a professional.

4. Am I investing enough in my communication and personal finance skills?

We have to stop using the term ‘soft skills’.

‘Soft’ implies that somehow these skills are secondary and merely supportive to ‘hard skills’. I beg to differ. ‘Soft skills’ – like learning to communicate effectively and managing one’s finances – are so critical that I’ve always wondered why they weren’t given enough of a spotlight in schools.

Communication, for one, is a skill essential in everything from writing an application letter to knowing how to interact on a first date. If you look at the advice of business magnates and leaders, one common thought they’d share is that you have to improve your communication skills. Legendary investor Warren Buffett says of communication, “If you can’t communicate, it’s like winking at a girl in the dark–nothing happens. You can have all the brainpower in the world, but you have to be able to transmit it. And the transmission is communication.”

To learn to improve on this skill, I read books like the seminal How to Win Friends and Influence People by Dale Carnegie and watched speeches like this funny and memorable TED Talk on creativity and education by Ken Robinson. But to actually improve on this skill, I had to seek multiple opportunities to speak in public, write to convince and influence, sell, and practice, practice, practice (and this is where #1 and #2 come in).

On personal finance, we all know that money isn’t the key to long-lasting fulfilment and happiness, but it is an important aspect of our lives. Managed in the right way, financial security helps us ensure our daily needs, physical health, and general well-being for years to come. And yet, personal finance is a topic barely ever taught to students; it seems that we are taught to produce fruits from labor, but we are not taught how to keep those fruits, how to make more fruits, or how to get the most nutrition from each fruit.

Lacking formal instruction on personal finance, I had to learn on my own. In university, I learned a little about how to save money, budget for expenses, and invest in the stock market, but many students would benefit by starting even earlier (a good book to start with one’s financial knowledge journey would be Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert Kiyosaki). Learning to save, spend wisely, invest in different options, and weigh risks and returns early on would allow young people to have sound financial instincts once they start earning more money after graduation

5. Am I taking in different viewpoints, or am I embedded in communities that just echo what I know and believe?

I was lucky to study in a university that was home to students of different socio-economic backgrounds, political beliefs, and faiths who were spread out among a variety of fields of study, artistic pursuits, and interests. But even so, it was easier to stay within my comfort zone and hang out with people who talked, thought, and acted like me.

Luckily, I was involved in extra-curricular activities and in NGO field work which pushed me to engage with people from an even more diverse set of age groups, backgrounds, and nationalities. Learning to navigate and appreciate this richness in perspectives allowed me to be better at managing diverse teams as a professional and communicating with people who do not talk, think, or act like me. However, there were still opportunities I regret not taking which, in retrospect, would have further pushed me from my ‘social comfort zone’.

More than helping one professionally, this question will also allow students to nurture independent thinking, empathy, and compassion – three values which, in our world today, have become more important than ever.

Getting to know many different versions of others also gives students an opportunity to find their inner voice. This thought is echoed by Ruth J. Simmons, the first African-American president of an Ivy League institution (Brown University), who shared in a 2014 Commencement Address:

“One’s voice grows stronger in encounters with opposing views… The collision of views and ideologies is in the DNA of the academic enterprise… For all of you who will inevitably become leaders, gird yourselves for moments of criticism, doubt and challenge. Take the time to discover who you are in the fullness of your intellect, identity and abilities because you will need to stand your ground effectively to be credible leaders.”

6. Am I learning and practicing good values?

“Your beliefs become your thoughts,

Your thoughts become your words,

Your words become your actions,

Your actions become your habits,

Your habits become your values,

Your values become your destiny.“Mahatma Gandhi

Our personal values form the cornerstone of how we see ourselves, how and why we act, and where we aim to go. Without a grasp of what these values are, we run the risk of letting others define our personality and purpose.

That’s why it’s sad to see components of schooling such as “Values Education” pushed to the sidelines. It’s equally sad to see classes in philosophy, literature, and art devolve to rote and mechanical learning modules when, in fact, these classes can actually influence our inner lives in a myriad of ways (watch Dead Poets’ Society to see this in action).

But learning and practicing values is much easier said than done. To discover my own values, I had to ride the highs and lows of both my academic and my professional life and then see what aspects of them were more important than others. I had to try different things, leave my comfort zone. I had to meet different types of people and see which ones had the attitudes I aspired to have. I had to get at the core of what values are and take a second look at the philosophers and writers I used to ignore as a younger student.

In other words, I had to go through #1-#5; produce successes; produce more mistakes; and then go through them again. And in evaluating and re-evaluating myself based on this final sixth question, I’ve now settled upon a set of values that I know I’ll still be re-visiting many times in the future.

Out of these values I’ve strived to practice, the one that I’d like to share here is: continuous growth. Cultivating a mindset conditioned to growth has allowed me to keep learning, to be critical of myself, and to aim to connect better with others. Striving to grow lies at the foundation of these six questions and strikes at the heart of what the education system really is for. Because students are not placed in a school just to become workers or professionals, to learn a trade, or to conform to the society around them, they are placed in a school to grow holistically as members of communities and societies.

And the beautiful thing about this is that when students and individuals grow, society grows too.

Conclusion

“Children must be taught how to think, not what to think.”

Margaret Mead

The pandemic has taught us many things, such as: what happens to one person or to a few people can affect up to thousands and millions; a society’s values can define its policies for its citizens and can define the kind of leaders it has; a crisis exposes what’s wrong with the world but can also expose what’s right; and no community or country, no matter how powerful, can stand on its own in the midst of a global problem.

In all these things, there are lessons being taught. Forgetting those lessons will mean making present and future generations vulnerable to the unprecedented hardship and heartbreak we’ve seen in the past months.

If we don’t want to forget, if we truly want to make a better normal for the world, then let us make a better normal for education too.

Thank you for this article. I really enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Thank you! Glad it helps you!

LikeLiked by 1 person